Cotton Road

Some of my fondest memories are of my grandmother and the farm. She left us with some mysteries to solve, and they pointed back to cotton.

In 2004, my grandmother, Bessie Barron Mercer, passed away. She was the epitome of the “diamond in the rough.” She was a tough, poverty-stricken, loving mother who spent most of her life improvising care and comfort for others. As one neighbor put it, “I can hear her singing across the cotton field.” And her laugh! It cascaded across the fields like the call of the pileated woodpecker.

For most of us, the starting point at which we first encountered Bessie, or Mama, was on the farm in Southeast Missouri, just south of Poplar Bluff, Missouri near the Arkansas border. The nearest village was Neelyville. Otherwise, it was as flat as far as the eye could see, nothing but one farm after another. It was there that our parents would drop us off for a couple of weeks or even longer, giving her grandkids an opportunity to learn of life in a place far distant from the comfortable, more urban homes in which we lived. The place was a working farm, so it was not always the most amusing place to hang out. It was hot and dusty. We were assaulted with the smells typical of dairy cows and hogs, entertained by chickens and assaulted by a mad rooster. But it would fill our minds with mountains of memories, a world that has long since passed.

Behind it all were two rather mysterious people: Bessie and Bill. Mama and Papa, we called them. I can still see them getting ready for the day, usually at an ungodly hour. Later in life I would discover that breakfast was a meal my grandparents ate after the morning chores were done, all the while I was sleeping. Even though they had a gas stove, Mama would still stoke up a fire in the wood-burning stove and artfully handle the hot burners on which cast iron skillets would be placed. It was a hearty breakfast of sausage and eggs, with homemade biscuits under gravy. But it was the ritual of the event that intrigued me. I can still see Papa spilling a small portion of its steaming hot coffee onto the saucer, swishing it around just a bit before sipping the coffee from the saucer. Then there was the hard block of butter, something I never saw in the grocery store. He would take a thick slice of the stuff and chop it up, mixing it with homemade jam, then spread it over his biscuits.

They were particularly religious and it was interesting to see how their faith intersected their lives. It was rather boring and a bit bizarre, but the long rides to Naylor, Missouri to their church was at least a change from the monotony of farm life. It would be there that I would discover that Mama could play a piano, that they would sing songs that were not in our hymnal back home, and shout out prayers and “Amens” without reserve, as I would nestle under one of Mama’s handsewn quilts attempting to find a comfortable position on the wooden pew. They would afterwards have a Sunday dinner, not at a restaurant, but at one of their farms. They never went out to eat.

Bill would die in 1968. It was a sudden heart attack. It was also the end of a chapter in our lives. Bessie couldn’t run the farm. It had to be sold. I would not be returning until the early 80’s, and then rarely afterwards. Bessie would move to Mississippi and go on to live to be a hundred years old, passing away during Hurricane Katrina. In that time she enriched our lives with her presence, and left me with more questions than answers. One thing she would often say is that they moved from Oxford, Mississippi because of the boll weevil. As she slipped into the debilitating influence of Alzheimer’s, she would often repeat that story to others, and kept mentioning the “big white house” they left behind. That “big white house” piqued my curiosity and I set off on a journey to discover what she was talking about. Did that house still exist? Were the Barrons (her family) landholders? If so, did they own a plantation? And being in the Deep South, the question that was unavoidable was whether they owned slaves?

On this journey I had five objectives. I wanted to see my grandmother’s grave, proceed to Oxford, then at least take a look at Dyersburg, Tennessee to see the place they migrated to, and then move on to Wardell, Missouri to check on my grandfather’s grave. Finally, I wanted to see the farm, the place I spent many memorable summers.

Grandma’s Grave

My grandmother died during the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. She was a hundred years old and quite fragile. They evacuated her home one block from the beach in Long Beach, Mississippi and moved her to Pensacola, Florida to a nursing home where she passed away a few days afterwards. After the personal care and space she had in her home in Long Beach, she must have certainly experienced the disorientation and loneliness of a nursing home, but under the circumstances of that natural disaster, it was the best that could have been done for her. She was buried later in Long Beach.

I was in Alaska at the time and it was nigh onto impossible for anyone to travel to the Gulf Coast unless you had property in the area. I recall attempting to make travel arrangements, only to discover that both train and air traffic were either not permitted or severely limited. I was disappointed in not being able to say good bye to grandmother in the traditional way, with a graveside service and the reunion of extended family. But there were no such luxuries at that time. Even burials were suspended being that many cemeteries remained inaccessible. So where she was buried was unknown to me for ten years.

I found her marker, a simple stone flush with the ground, probably the most fitting testament to her life. It was shaded by pine trees, resting in a well-maintained cemetery. I later visited the site of her last home. It was gone, one of the many homes destroyed in the hurricane.

Oxford

I arrived in Oxford, Mississippi in January, 2014. Everyone I talked to said you need to enroll on Ancestry.com. That is somewhat expensive and, besides, what’s the fun in that? My question revolved around property, that “big white house.” So I headed to the Recorder’s office and browsed through a few decades of deed registrations spanning the period of 1835 through 1920. Only one record of a Barron. It was a conveyance issued in a will. The man had died and left a conditional tenancy to several individuals, most likely in exchange of caring for his widow. One of those people was a Vic Barron (short for Victoria). She had married a TJ Barron. Vic Barron was a witness and WJ Barron was a notary public. “WJ” was Bessie’s father, usually referred to as Jesse.

TJ was not part of the immediate Barron family that Bessie belonged to, but there were only two lines of Barrons living in Lafayette County, as best as I could surmise from my research. It was the only hint of residence I had of any Barron. Later study of the census record showed the Barron families lived next to each other. With that knowledge, it led to some credence that the location described in the conveyance would point to the general area where they lived.

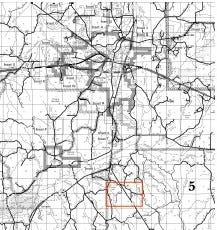

The parlance of plot assignments was NE ¼, Section 9, Township 10, Range 3 West, 160 Acres of an area also referred to as the Widow Duke land. Maps at the Recorder’s office show the Range lines (basically longitude), crisscrossed East to West by township borders, each township divided into four sections, each section divided into four 160 acre quadrants. Some people wonder what the magic of 160 acres is about, but it was the confluence of navigational math and the idea of a full-time farm in 1787 when surveying standards evolved in the United States. So what Mr. Duke had left to his widow was probably the full-size farm granted to the original settlers in the region.

I found the location of the “farm” and it only deepened the mystery. It was hilly and blanketed by oak forest. This was definitely a far cry from the flat cotton fields I expected. I went away thinking that I might have to revisit the deeds office and do more research. Recordings have been known to be in error, but at this point I was running out of time and had to move on. My next question was “Where is the best place to grow cotton?” To be honest, I did not see any prime farmland in Lafayette County, yet a quick glance at its history shows it was a rich agricultural land. Where did it go?

I was somewhat at a loss of where to go next. I had obtained considerable information at the Lafayette County genealogical society, attached to the city library. But I returned to the hotel uncertain where to proceed next. The next morning it occurred to me where the best place was to find local information: McDonalds. Just as I expected, I arrived at the restaurant and found sitting around a long table of bunch of old men drinking their free coffee. After eating my breakfast I asked if I could join them. Turned out one of the men was a retired US Forest Service ranger (I worked for the USFS in 2014). I informed them of my project. One of the men smiled and suggested I check out the extension service. I went over to the county extension office and they pointed me to the USDA Soil Research Lab which was not far from the University of Mississippi campus. It was there that the truth became known.

What Ancestry.com cannot provide is Seth Dabney. About my age, he came to me draped in decades of knowledge on Lafayette County’s soil. He produced a book last updated in 1981. Within was a color map. Most of the county was covered in yellow which signified a type of soil. This type of soil covered the quadrant in question. Under prime conditions, this soil would have about a meter of rich topsoil, followed by sand. Seth’s question to me was when, and I stated 1915. He smiled and replied, “In 1915, Lafayette County was experiencing desertification.” About every inch of land was being farmed, and they grew cotton everywhere, even on hilly ground. At that time the top soil was being depleted and many farms were being abandoned. The exposed sandy soil was not treated with ground cover and the result was a broadening expanse of desert ground. In essence, the boll weevil in Lafayette County was merely the nail on the coffin.

In conclusion, further study of the census record would be required to piece together the plots of land owned by various individuals in the area. This could help determine where the Duke property resided and the surrounding families and structures. The “big white house” that Bessie referred to may have been the brief interlude in her history where she lived in a relatively fine house. Victoria was a daughter of JH Cook (to whom the conveyance was issued) and it is conceivable that the Barrons may have inhabited the house and cared for the widow and her farm.

Bessie’s father was Jesse Barron. How this may have pertained to his family is not clear, but one thing gleamed from the oral history of my mother and others in the Wardell area was the tendency of families to allow their children to reside in other homes. Lautain, Bessie’s second daughter, lived in a home in Wardell so as to babysit full time the children of the local doctor. Erlene Hampton, later Miller, was a niece to Bill and Bessie Mercer and she often lived in their home to escape what may have been an abusive situation. So it is not surprising to discover that Bessie may have lived in the big white house at times, assisting Vic Barron.

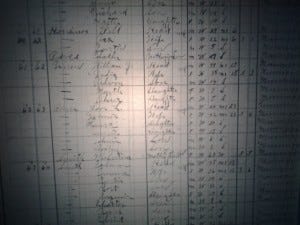

Return to Oxford

There were simply too many questions left unresolved from my first trip to Oxford. So the following year I returned. Oxford was a wonderful town. I revisited the Recorder of Deeds office, double-checked the conveyance as well as another review of records. What I discovered the previous year was confirmed to be accurate. I returned to the library extension that held old records and reviewed the census records from 1912. As I read down the page the families that lived along that country road seemed to come to life. I counted 47 residences. Today? I couldn’t recall, but maybe four or five homes now remained on that road. So you could imagine that in 1915 the dusty road now labeled as County Road 3011 on the map had a large white house inhabited by the widow of Mr. Duke, with Victoria Barron assisting the widow, tagged along by an eleven year old, skinny girl with dark hair. And along that road were numerous tenant farms, of which one was that of Jesse Barron and his wife, where Bessie Mercer lived.

………………..

Read more of Cotton Road. What follows are my discoveries of where the old house may have been located, the lay of the land, and her journey from Oxford to Dyersburg, Tennessee, onward to Wardell, Missouri and eventually to Coon Island.

© Copyright 2024 to Eric Niewoehner