Before Lawrence: James Lane

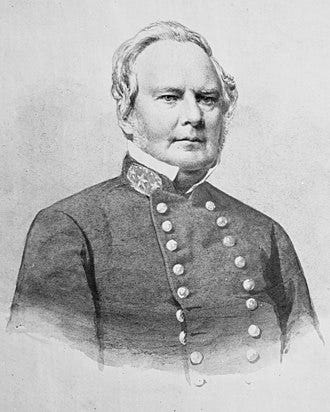

The sixth chapter of Before Lawrence introduces James Lane, the leader of the Kansas Brigade.

This is the sixth chapter of Before Lawrence. To learn more about the purpose of writing this story, check out the “Forward.” Before Lawrence is part of The Missouri Chronicles. Follow the story by subscribing on Substack, contribute your thoughts, and check out the added resources.

Before General Beauregard fired the first cannon shot into Fort Sumter in April 1861, there were the sorts like James Lane and John Brown. These two men had come west into Kansas as part of a greater cause: to end slavery. And that, in a nutshell, was the fundamental cultural difference between the town of Lawrence, Kansas and the town of Osceola, Missouri. Everyone who lived in Osceola came to the country to pursue a new life, carving out an existence in a rugged wilderness. Settlers would spread to the prairies that surrounded the Osage River basin, but the hub of business would be in towns nestled in the hills along the river. The only cause these people were concerned about was the pursuit of happiness, the desire to have a place of their own and a sustainable life. For some, it included bringing with them slaves. But for almost everyone, it was a matter of hard, rugged work. With the probable exception of a dozen men in Osceola, everyone worked with their hands, whether they owned slaves or not.

And, to be fair, the same could be said for Lawrence. The unfortunate consequence of the Compromise of 1850 was that settlers coming to Kansas came for the exclusive purpose of advancing the right to own slaves, or to abolish that right. Yet when they arrived in this remote prairie, they found the land both inviting yet peculiar. Kansas was not Ohio or Missouri. It was drier. There were few trees. The surrounding prairie was teeming with buffalo. Surviving was what mattered. For most, it would take all their energy and time to survive. In that sense, the average settler who lived in and around Lawrence had the same struggles, hopes and disappointments as the people who came in the 1830’s and 1840’s to establish Osceola. Yet it was clear after a year or two that Kansas was not like the northern states they had migrated from. What grew well in Ohio struggled in Kansas. Regardless, there was no end of enthusiastic settlers, passionate over the cause of abolishing slavery, and confident that they could overcome the obstacles that nature put before them.

Draped over their struggle to survive was a conflict that clouded their daily existence. For some, it wasn’t enough to express your opinion, or to simply vote. It was incumbent that words be backed with actions. From the beginning, it was clear that meddlers from Missouri had crossed over the border to interfere with elections. Armed men surrounded the voting stations, intimidating abolitionist voters. In the end, Kansas was endowed by an “official” pro-slavery government installed by three times more voters than residents in the state. A competing government was established and remained so until the pro-slavery administration had been removed. This merely served to fan the flames. The conflict intensified when men began voting with bullets rather than ballots. It is hard to say who started what, but local conflicts spilled over the Missouri border. From that state came ruffians who took matters into their own hands. Bushwackers they called them. The pro-slavery element crossed the line when they burned down the fledgling village of Lawrence, Kansas in 1856. The abolitionists responded with nothing more than naked, cold-blooded murder. The sorts like John Brown salved their moral souls by ambushing isolated slaveowners on their farms, murdering them in their fields or before their families.

It was these sorts that attracted a different sort of settler, the kind that would forever redefine the West. They were restless – and often broke. The West was a land of boundless opportunities and it would be young single men who would come and attempt to make the most of it. These young men would discover that crime could pay. They veiled their criminal activity with abortionist zeal. It would be these sort of men who would become “soldiers” of the Kansas Brigade.

What kind of man would lead this band of criminals?

James Lane was a born leader. He commanded two regiments during the Mexican-American War. He was elected to Congress while residing in Ohio. But in 1855 he came to the state of Kansas to advance the cause of abolitionism. An effective speaker, he proved to also be an activist and organizer. His political star quickly rose in Kansas and by 1861 he was a US Senator from the state of Kansas who quickly became a favorite of Abraham Lincoln. Understandably, Lincoln was looking for strong, ardent allies as the nation descended into civil war. Lane was such a man. Lane wanted to get into the fight. Lincoln was happy to grant it to him. Lane had military experience, so he should have the skills needed to organize and supply his troops and to lead men into battle. Lincoln needed military leadership in Kansas to flank the troublesome insurgency in Missouri. Lane was commissioned as a brigadier general.

Yet things were not as Washington perceived. Many in Kansas, the governor in particular, recognized that they were isolated from Union military support and dependent on access to the Missouri River for provisions, and were not keen on picking a fight with the Missouri State Guard. If Price would choose to invade Kansas, there was little to stop him. Kansas had to move cautiously.

Unfortunately for James Lane, the telegraph had this capacity to relay to Kansas political and military news in a matter of hours. Lane, departing Washington immediately upon receiving his commission, would arrive in Lawrence not as a hero, but as a political pariah. Governor Robinson knew the man for what he was: impetuous and unscrupulous. He considered assigning Lane a command a mistake. Lane was notified that since he was now commissioned as a brigadier general, it was the governor’s duty to appoint a replacement as senator.

Lane was furious and he told the governor he would relinquish his commission. He returned to Washington, resigned from his commission and proceeded to take his seat in the Senate. He then later returned to Lawrence in early August with no official military designation. Yet for some strange reason he would march into Missouri as a military officer. Or was he? Thus was the ambiguity of war where a nation was literally improvising itself into one of the greatest conflicts of the 19th century.

Aside from St. Louis, what amounted to the largest city in Missouri began to march northward from Springfield in the last days of August 1861. Under the leadership of General Sterling Price and Governor Claiborne Jackson, its government in exile and operating out of Springfield, an admirable army was pieced together. Called the Missouri State Guard, it would eventually comprise 15,000 men. Aside from the infantry itself, nearly half that number of personnel was needed to transport the provisions. Nothing like it had ever been witnessed in the state. It’s path would take it to the small village of Osceola. There it would be fully provisioned for the march to the Missouri River and to the heart of the confederate cause in the state.

Yet the Union forces had not all run back to mama. While they were certainly discouraged, they were not destroyed. They had fought well at Wilson’s Creek, the place where the battle had taken place outside of Springfield. But it would be the confusion of battle that would be their downfall: the heat, the lack of experience, the dense clouds of smoke from the black powder discharge, and the lack of distinguishing uniforms. Yes, both sides looked the same under those circumstances.

While General Fremont in St. Louis was licking his wounds and declaring martial law, Price’s march to Lexington threatened to isolate Kansas. This was no small thing. Kansas was not a rich agricultural state like Missouri. It was also a very young state. The people of the state were highly dependent on the supply line from the East.

And while it was clear to some that Price was heading to the Missouri River, during the last days of August there was no assurance he would march straight north. The easiest terrain was on the Missouri-Kansas border. It was conceivable that Price could veer to the west and take out one Union outpost after another. The so-called Kansas Brigade was determined to not let that happen. Leaders in the state knew they were on their own and they were determined to make Price’s march as difficult as possible, even though vastly outnumbered.

So it would be that “General” James Lane left for Fort Scott, Kansas with an undetermined number of men. In his mind, he feared an attack on Fort Scott, a distant outpost in southeast Kansas. But the first order of business was to find Price’s army. Estimates were that Price’s army numbered 10,000. Lane knew the odds were considerable, but if he chose his battle, he could hit them where they were most vulnerable and then return to Fort Scott.

Judging from the nature of his “brigade,” it was doubtful he had any idea as to the number of troops he had under his command. He could count on 600 men, but as the brigade was forming and leaving Fort Scott an undisciplined, drunken rabble of the worse sort seemed to join their ranks. Lane was ambivalent, but he needed every man he could find, and this sort was the sort that knew how to handle a firearm.

This is what the Civil War was leading to, a brigade of brigands, led by a rash politician, favored by a president who was desperate for any measure of support.

© Copyright 2024 to Eric Niewoehner

Previous Chapter: August 19, 1861

Next Chapter: September 2 — The Battle of Dry Wood Creek

Your comments are welcome. Feel free to send a message.

This is the best description of the situation in Kansas/Missouri as the Civil War began.